In line with International Medical Corps’ global strategic objective to improve, maintain and scale up highly accessible, high quality Mental Health and Psychosocial programming, a burnout prevention (self-care) program for carers at IMC Afghanistan’s Mental Health Hospital (MHH) in Kabul.

Through sustainable healing methodologies, I conducted mindfulness training for MHH’s mental health staff. This training intended to build on existing positive coping strategies and self-help tools to overcome stress and support positive coping mechanisms of staff. By helping trainees become familiar with their own psychological, emotional and social reactions to trauma, stress and relevant co-morbid conditions (i.e. fear, grief, stress, depression, anxiety), they can develop greater compassion satisfaction and burnout can be significantly reduced. This case study will highlight IMC’s self-care empowerment model, assessment results, lessons learned, and recommendations for improvement and replication in other countries.

Regarding staff working with the traumatized (e.g. doctors, mental health counselors, psychiatric nurses and psychologists) emotional exhaustion was present in 20% of expatriate staff from aid agencies and 10% of professionals.[i] Also, there is considerable evidence that the stress inherent in health care negatively impacts health care professionals.[ii] The researchers list numerous negative impacts from this stress including depression, decreased job satisfaction, psychological distress, and many other physical health problems such as fatigue, insomnia, heart disease, depression, obesity, hypertension, infection, carcinogenesis, diabetes, and premature aging.[iii] This phenomenon is known as compassion fatigue (CF).

CF also associated with decreased patient satisfaction, ‘‘suboptimal self-reported patient care’’, and longer patient- reported recovery times.[iv] Similarly, research shows that stress affects the quality of care through a decrease in attention, reduction in concentration, impingement on decision- making skills, and reduction in providers’ abilities to establish strong relationships with patients.[v] Studies were done on Canadian frontline health care workers (counselors, children’s aid workers, and emergency staff) and found that CF can manifest in the workplace and client relationship through chronic absenteeism, low morale and decreased quality of care.[vi] Further, White (2006) found that up to 50% of practitioners were affected by burnout stemming from CF.

Preventing Compassion Fatigue: Importance of Self Care

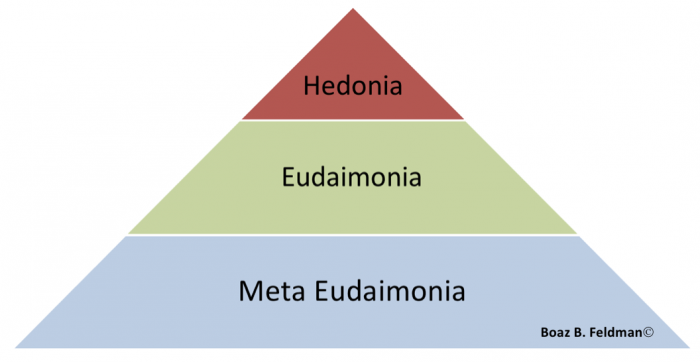

Despite the prevalence of CF in the field of social work, researchers have suggested that CF is not only treatable, but preventable.[ix] The ability to address CF before onset would allow trauma practitioners to provide consistent high quality care. Empirical studies have shown that there is a circular relationship between CF and self-care.[x] They stated that “professional caregivers tend to be very good at caring for others, while often neglecting and failing to recognize their own needs” (p.4). Research shows that clinicians who make a conscious effort to look after their own well-being are not only less susceptible to CF, but have a greater sense of compassion satisfaction.[xi] Research indicates that having a higher level of compassion satisfaction (getting satisfaction out of helping others) enables clinicians to be more effective in treating their clients. A major contributing factor to the development of compassion satisfaction is self-care.[xii]

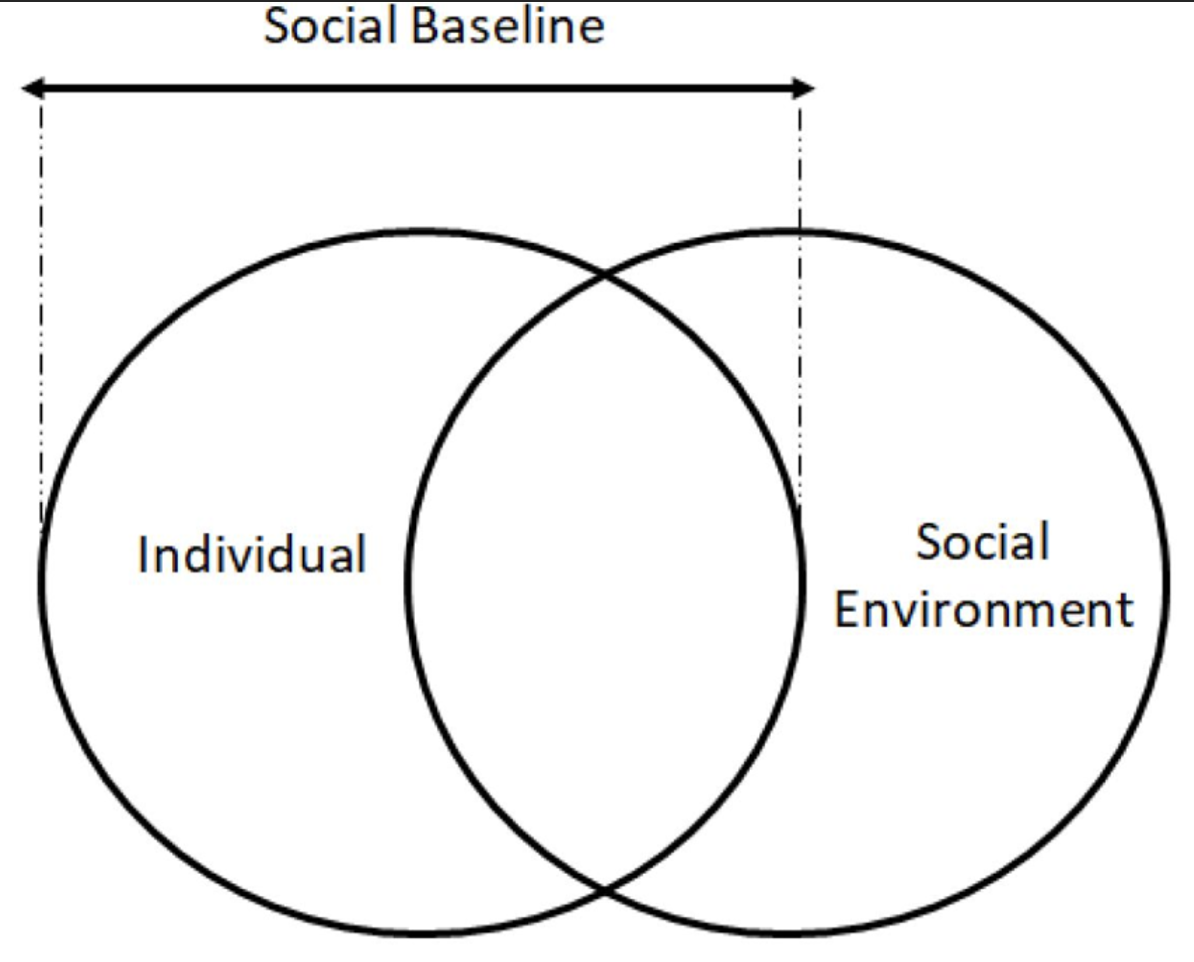

Self-care is defined as an unbiased observation of one’s inner experience and behavior, as well as the responses that counterbalance negative factors. Facets of self-care include self-awareness, self-regulation/coping, and balancing of self and others interests[xiii]. Examples of self care include psychotherapy for the caregiver, supportive work environment, proper supervision, and peer consultation. In addition, contemplative (meditation, mindfulness and self reflection) techniques have been highly successful in the reduction of burnout.[xiv]

The Mindfulness-Based Counselling (MBC) program was originally planned as a 3-phase Training of Trainers (ToT) intervention: (i) mindfulness self-care skills, (ii) Mindfulness-based counselling skills, (iii) trainer’s module. Since it was a pilot project, and due to the finishing assignment of International Medical Corps (IMC) at the MHH, we completed only the first phase of the intervention (self-care).

Training Objectives

The objective of the intervention was to develop and strengthen IMC’s mental health self-care strategies, as part of the rehabilitation program of quality hospital standards of MHH. Through sustainable healing methodologies, Mindfulness training was conducted for MHH’s mental health staff. This training intended to

- build on existing positive coping strategies and self-help tools to overcome stress and

- support positive coping mechanisms of staff. Also, the training aimed at

- helping trainees become familiar with their own psychological, emotional and social reactions to trauma, stress and relevant co-morbid conditions (i.e. fear, grief, stress, depression, anxiety),

- while respecting the Islamic cultural context and making specific reference to it.

- be planned over three phases, two of which were distance-based.

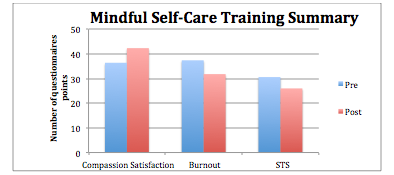

Overall, the training evaluations indicated a positive outcome for the training. Compassion satisfaction and mindfulness skills were increased, burnout and secondary traumatic stress were reduced. Since self-care was a new methodology and way of practice the counselling profession, it was a challenge for participants to value that by taking care of themselves, the services they provide to the beneficiaries are positively affected. More specifically, mindfulness practices were well received and understood, and the small group distance-based format of the training worked well with uninterrupted skype conferences.

For the full report, please click contact Boaz here.

[i] Ehrenreich, J.H., & Elliott, T.L. (2004). Managing Stress in Humanitarian Aid Workers: A Survey of Humanitarian Aid Agencies‟ Psychological Training and Support of Staff. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 10 (1), 53-66

[ii] Connorton, E., Perry, M. J., Hemenway, D., & Miller, M. (2012). Humanitarian relief workers and trauma-related mental illness. Epidemiologic reviews, 34(1), 145-155.

Shapiro, S.L., Astin, J.A., Bishop, S.R., Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management,12(2), 164-176.

For a review, please see Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 15(2), 61-66.

[iii] Spickard A, Gabbe SG, Christensen JF. (2002). Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288:1447–50.

[iv] Antares Foundation, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Managing Stress of the Humanitarian Aid Worker: Working Conference ‘Progressing the Tasks’. Retrieved April 5, 2015, from http://www.antaresfoundation.org.au/images/downloads/Conference2/2004Managing%20Stress%20of%20the%20Humanitarian%20Aid%20Worker.pdf

Ehrenreich, J.H., & Elliott, T.L. (2004). Managing Stress in Humanitarian Aid Workers: A Survey of Humanitarian Aid Agencies‟ Psychological Training and Support of Staff. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 10 (1), 53-66.

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Family Journal 2002;12: 396–400.

[v] Shapiro, S.L., Astin, J.A., Bishop, S.R., Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management,12(2), 164-176.

[vi] White, D. (2006). The hidden costs of caring: What managers need to know. The Health Care Manager, 25(4), 341-347.

[ix] Figley, C.R.(2002). Compassion Fatigue: Psychotherapists Chronic Lack of Self Care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1443-1441.

[x] Simon, C., Pryce, J., Roff, L., & Klemmack, D. (2005). Secondary traumatic stress and oncology social work: Protecting compassion from fatigue and compromising the worker‟s worldview. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 23(4), 1-14.

[xi] Krause, V. (2005). Relationship Between Self care and Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue and Burnout Among MentalHealth Professionals Working with Adolescent Sex Offenders. Counselling and Clinical Psychology Journal, 2(1), 81-87.

[xiii] Barnett, J. E., Baker, E. K., Elman, N. S., & Schoener, G. R. (2007). In Pursuit of Wellness: The Self careImperative. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(6), 603-612

[xiv] Linley, P., A. & Joseph, S. (2007). Therapy work and therapists‟ positive and negative well being. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 384-403.

Shapiro, S.L., Astin, J.A., Bishop, S.R., Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 164-176.