Boaz’s Blog

Welcome to Boaz’s blog page.

Every month (except when on intensive silent mindfulness retreats) Boaz writes a report on ongoing resilience-oriented activities in humanitarian interventions and the world of Mindfulness practice. The areas of intervention are wide-reaching, and reflect Boaz’s scope of activity and interest. These reports are about 500-700 words long. Enjoy!

Relational Dharma – « I am because we are »

31 mars 2022

Relational Dharma – « I am because we are »

Too many approaches in meditation are overly self-serving and excessively navel-gazing, placing one’s individual self at the center of both one’s suffering and liberation. This solipsistic tendency is a rampant consequence of over 200 years of post-Euroamerican Enlightenment: “cogito ergo sum – I think therefore I am” said Descartes. This needs to be adapted according to the latest social and affective neuroscience.

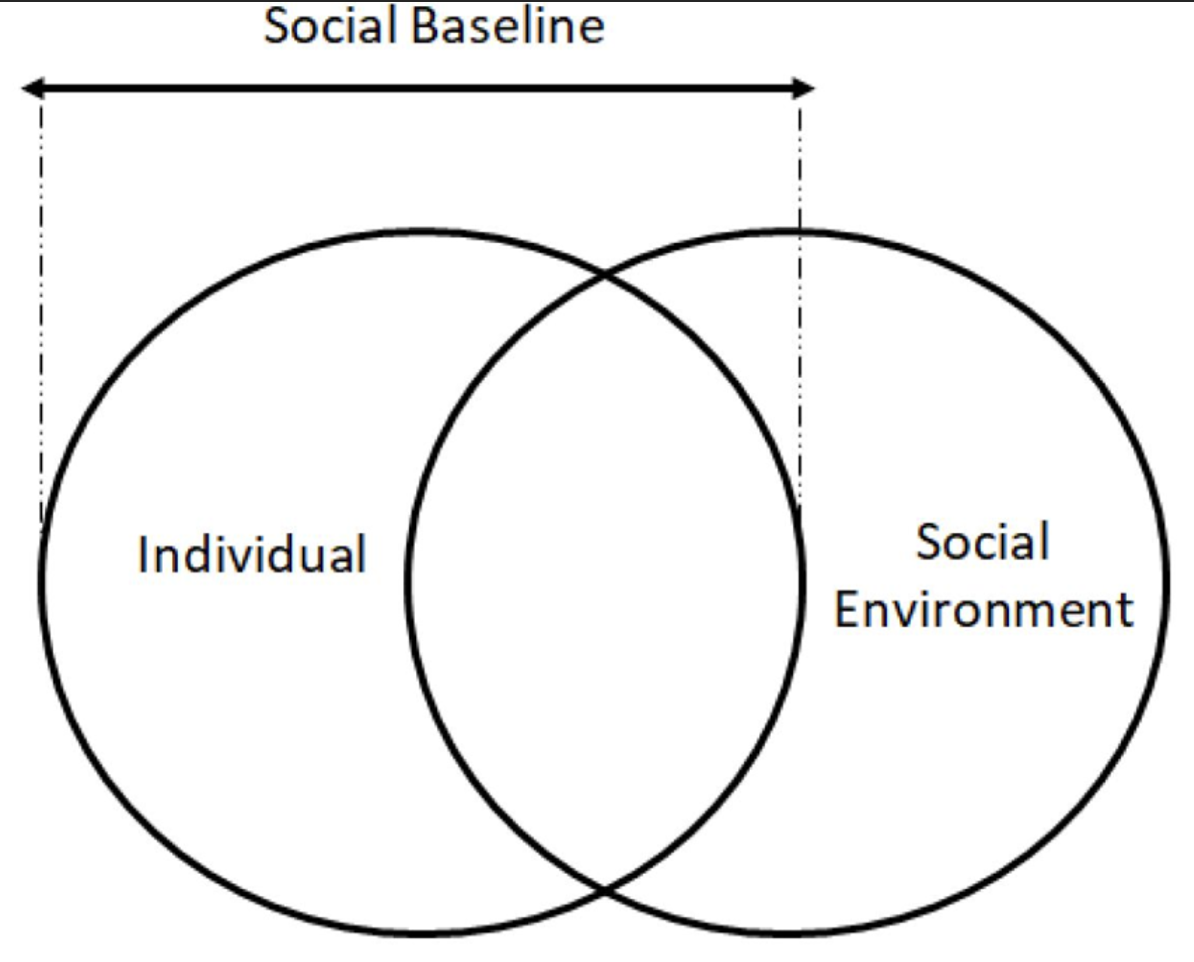

It has been empirically shown that our sense of self is not a fixed, reified and singular construct and experience. The Social Baseline Theory (SBT – Coan & Sbarra, 2011), for instance, shows that the way we conceive of our self is based on who we have around us. We are constantly evaluating the quality of our social environment and making judgments as to how much physiological resources (i.e. glucose) we need to use according to the task at hand. For example, if I have a few good friends around me, the bio-energetic cost of going up a hill will be less than if I am alone. In SBT they say our individual self then merges with others and forms a wider sense of a social sense, of which we become a part: “I am because we are” (Ubuntu saying).

This shows that we evaluate threats and risks as being less dangerous with good friends (I know, it sounds so obvious now). However, most meditation circles in the West promote individual practice! In effect, they are encouraging us to go up that hill alone, which makes the difficulties we encounter in meditation be perceived as more difficult than if we were travelling with friends. Evolutionarily, we have become accustomed to be in the presence of others and therefore the baseline for feeling safe and well is to be a part of a larger pleasant social environment.

Figure 1. The individual & social environment overlap represent social baselines

(Gross, Medina-DeVilliers, 2020).

There is an overwhelming consensus in social and now clinical psychology showing that relationships are the most important factor, and by far, to build resilience and psychological health. Moreover, all of environmental safety and ease created by our peers frees us from having our hypervigilance neural networks online, and allows us to focus and ground ourselves deeper in our internal experience. This is why, at NeuroSystemics Dharma, we emphasize social meditation.

We make a lot of efforts to build a safe and compassionate community to support one another through the challenges of meditation. How difficult is it, for instance, to even take 15-20 minutes a day to sow down and practice? Very difficult for most of us. It’s challenging being with ourselves and develop these meditative skills of mindfulness, compassion, friendliness, joy and equanimity. Buddhist texts talk about “going against the stream” of our habitual patterns, and that takes effort. This effort is perceived as being less work if we do it together.

In our monthly 1.5h Dharma Gatherings we teach meditation and practice in a community (like we used to before the modern industrial age). Our approach combines ancient Buddhist teachings with modern neuroscience and systemic analysis. To learn more and join us sign up here!

Many blessings and look forward to seeing you there.

Boaz

The power of meditation for mediation

30 avril 2019

The power of meditation for mediation

Mediation is often very difficult work. As mediators, we are called upon to help resolve conflicts that often seem intractable and sometimes involve destructive emotions or even physical violence. To do this work, we must stay calm and grounded. If we are to help heal the parties and the situation, we must be detached, fully awake, open and present. We also need the ability to stay flexible and move in any direction. Meditation is a tool for developing these qualities.

There is ample scientific evidence demonstrating the positive effects of meditation and other contemplative practices (such as yoga and qigong) on the human body. Among other things, there is substantial research that proves that meditation induces what Herbert Benson, MD calls the « relaxation response. » Few scientists now doubt that these practices decrease stress hormones, blood pressure and pulse rate.

However, meditation does more than simply improve physical health. It has been reported that meditation increases the tranquility of the mind, improves perceptual abilities, and promotes a detached neutrality. Most significantly for mediators, Western science has now confirmed that meditation has the ability to transform destructive emotions. For example, by using devices that image the brain during meditation, Dr. Richard Davidson of the University of Wisconsin has found that people who practice meditation become calmer, happier, more loving and less prone to destructive emotions. Moreover, one does not have to be a monk (or even a Buddhist) to benefit from practicing meditation. To the contrary, Dr. Davidson’s research has indicated that meditation is very helpful for ordinary people, and that the parts of the brain that help to form positive emotions become increasingly active after only eight weeks of meditation.

The question then becomes – what are we as mediators to do with the information that meditation has the ability to transform negative emotions? In addition to using meditation to develop our own qualities, we should consider whether it would be appropriate to encourage the parties embroiled in the conflict to meditate. The answer to this question depends on our view of the role of the mediator.

While there are dozens of personal benefits that flow from meditation, experienced mediators may find, as I have, that Buddhist awareness, contemplation, and insight practices can enhance our professional skills as well. It is not uncommon, for example, for mediators who meditate regularly to experience the following benefits:

- Improved ability to remain calm and balanced in the presence of conflict and intense emotions

- Greater willingness to move beyond superficiality in conversation and move into the heart of whatever is not working effectively

- Expanded sensitivity to the subtle clues given off by the parties, indicating a shift in their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes

- Deeper insight into the nature of suffering and what might be done to release it

- Greater awareness of what apparent opponents have in common, though they emphatically disagree and even dislike each other

- Improved creative problem solving skills, and ability to invent or discover imaginative solutions

- Expanded capacity to calibrate and fine-tune insights and intuition

- Greater sensitivity to the natural timing of the conflict

- Increased willingness to engage in “dangerous” or risky conversations and raise sensitive issues without losing empathy

- Decreased investment in judgments, attachments, expectations, and outcomes

Increased ability to be completely present, open, and focused - Reduced stress and burnout

Register for the next Meditation and Mediation Training Program in Autumn 2019 by writing to Mrs. Salina at: salina@skwm.ch. For more info, please check this page.

How Mindful Leaders Develop Better Companies & Happier Employees

18 janvier 2019

Mindfulness is proven to help leaders manage their stress, which reduces employee stress, creates a better workplace, and improves the bottom line.

A recent study revealed that when leaders are stressed, their anxiety can be felt across the entire organization, often to the point where good employees will walk away from a job to save their own health. Only 7 percent of employees surveyed believe that their stressed leaders effectively lead their teams, and only 11 percent of employees with stressed leaders are highly engaged at work.

The study also found that when leaders fail to manage their stress in a constructive way, more than 50 percent of their employees perceive their leader as harmful or ineffective. Further when leaders are unable to manage stress, employees lose their drive to advance within the company.

One of the most effective ways to manage stress is mindfulness. When leaders actively engage in mindfulness practices, the « psychological capital » of an organization rises. There are 4 components of psychological capital:

- Hope: A positive motivational state that is based on an interactively derived sense of successful agency (goal-directed energy) and pathways (planning to meet goals).

- Optimism: Expecting good things to come, and reacting to problems with a sense of confidence and high personal ability.

- Self-efficacy: « Task-specific self-confidence, the belief that you are able to accomplish something effectively, » according to psychologist Albert Bandura

- Resilience: The ability to bounce back and beyond when faced with adversity.

How the leaders of an organization manage their own stress directly impacts the levels of these 4 components.

How Mindful Leaders Think

Mindful leaders have mastered 2 specific ways of processing:

- They are able to personally separate themselves from stressful events. They learn to not take organizational threats personally, and are able to observe situations from a neutral position, rather then becoming personally engaged.

- They are able to control their reactions to threats or difficult situations so that they can process their options, rather than reacting without thinking.

Harvard Business Review research identified 3 specific areas of mastery that allow leaders to be more present, more thoughtful in their organizational choices, and more aware of everything going on around them. The 3 areas are:

- Metacognition: This is the ability to take a step back to observe at a distance what is happening around you. By doing so, you become more aware of your own reactions to situations. « Without metacognition, there is no means of escaping our automatic pilot, » say HBR researchers.

- Allowing: This refers to being open to what is happening without judgment or yourself or anyone else. « Without allowing, our criticism of ourselves and others crushes our ability to observe what is really happening. »

- Curiosity: The most effective leaders have a strong sense of curiosity, and are open to learning more about all situations. They embrace the opportunity to gather as much information as possible before making any decisions. « Without curiosity, we have no impetus for bringing our awareness into the present moment and staying with it. »

Becoming a Mindful Leader

The first step to becoming a mindful leader is to develop self-awareness. We can not change what we don’t know. Leaders can raise their own mindfulness by paying attention to how they are showing up with people and within situations at work.

Once we become aware of how we are reacting and engaging, we can make a plan to improve our awareness and presence. One of the easiest changes we can make starts with our breath. A 5-minute breathing exercise every day will diffuse reactions and emotions.

In addition to become aware of our breath, there are many other tactics leaders can use daily to increase mindfulness:

- Checking ourselves emotionally before we enter a room or a meeting

- Taking a walk specifically to pause and re-center, also known as « walking meditation »

- Scheduling in downtime to recharge

- Integrating mindfulness into our daily lives is often easier said then done.

The Emotional Energy Starts at the Top

Creating a healthy, emotionally safe work environment has never been more important. As with everything else in a company, this initiative starts at the top. Leaders must remember they are always being watched.

What does your emotional presence tell your employees about you and the company?

Happy at Work Forum Special

16 mai 2018

Yesterday was a special day. My dear colleague Annika Mansson celebrated 10 years of founding her Happy & Work organisation. However, this is not just about her celebration, this is about celebrating the importance and worthiness of deepening happiness.

In the US Declaration of independence, which happens to be one of the most influential documents for the founding of Western democracy and participative politics, there is one code of particular relevance. It says that every citizen has the right to « life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. » Isn’t it interesting that the pursuit of happiness is given as much weight as the right to life and liberty? What importance does this have for business?

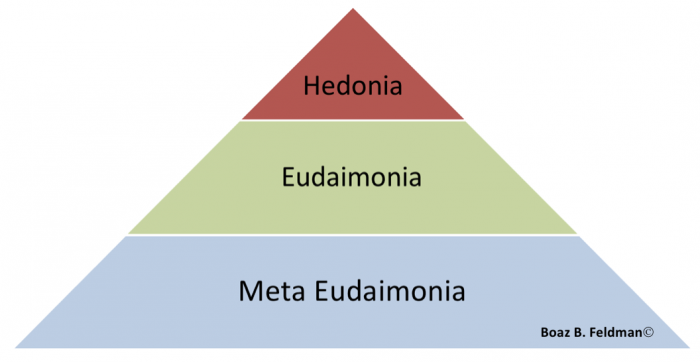

The management science literature is now populating with a growing number of articles on the topic of happiness and well-being. It started with organisational psychologists such as Frederick Herzberg and his hygiene and motivating factors. Today we are working towards a tripartite model of progressively more profound forms of happiness (see figure 1).

Firgure 1. Tripartite model of individual & organisational happiness

This model has a few Greek terms. First there is hedonic pleasure, which literally means « delight ». Think about a nice meal at the cafeteria, the deliciously tasting coffee next to the company elevators, the pleasure of working on an efficient computer. These are the small pleasures of life that an organisation can help with and make each day feel easier to get through. Second, there is eudaimonic pleasure, which we can brake down into « eu » meaning « good », and « daimon », which means « in spirit ». Imagine yourself immersed in doing something you enjoy, perhaps developing a project that fits your interests or engaging in a meaningful job. Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, one of the founding fathers of positive psychology, came up with the notion of « flow » which is when you are completely aligned with a sense of purpose and meaning in what you are doing, not seeing time pass or challenges as problematic. This is eudaimonia at its best.

Third, we have that same quality of depth and meaning, with the added layer of expanding it and sharing with others. The power of the collective is such that one’s satisfaction is multiplied and grows exponentially since it reverberates not just within yourself, but among your peers and natural environment as well. This form of happiness necessarily implies a sense of virtue and moral compass from Paolo Gallo (one of the keynote speakers of the forum). Since there is a growing alignment and coherence between yourself, your peers, society and natural environment at large, your actions naturally start to reflect needs and desires from a collective intelligence. Your own needs do not compromise that of the collective, but it rather becomes a mutually reinforcing and complementary process. Paolo told a story of Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala who was the most inspiring boss he ever had. She was Managing Director for the World Bank and was then offered a position as Finance Minister for Nigeria. She was battling against corruption in Nigeria and getting momentum when suddenly she received threats of death. She stood tall and kept battling. The criminals then threatened her family, to which she did not respond. A few days later, they kidnapped her mother, saying that if she did not leave the country within 48 hours, they would kill her. Ngozi replied by saying « you can kill her. I will find you. » and stayed in Nigeria to do her job. She was able to stay put and keep her focus because she was so well grounded on that 3rd level of happiness. Her work felt important and made a difference to her peers, her communities and the country at large. The sens of drive, passion and commitment allowed for even the most disturbing of difficulties to arise and not overwhelm her. A few weeks later her mother was found alive. What can we learn from this story? Is it possible for us to reach this depth of happiness, this profound connection to a sense of meaning?

One can consider this pyramid in the same way as one think of the food pyramid. Everyday, we need a set of ingredients in order to stay healthy: liquids, carbohydrates, proteins, vegetables, fruits and fats. How about we start considering our needs for happiness, our pursuit for happiness in the same way? Would it be possible to have a daily agenda to satisfy all three layers? Today is also a special day, if we make it so.

Time for integrity: Mindful Leadership on the rise

20 février 2017

I have been teaching Mindful Leadership at the MBA programs for the Trinity College Dublin Business school, and now that Harvard Business School professors are teaching the benefits of mindfulness, it’s perhaps fair to say the practice of mindful leadership has arrived in the corporate world. I would like to share here some exerpts from a book called Resonant Leadership by Richard Boyatzis and Annie McKee, Harvard Business School Press (2005), which help illustrate some of the key tenets of Mindful Leadership:

“Great leaders are awake, aware, and attuned to themselves, to others, and to the world around them. They commit to their beliefs, stand strong in their values, and live full, passionate lives. Great leaders are emotionally intelligent and they are mindful: they seek to live in full consciousness of self, others, nature, and society. Great leaders face the uncertainty of today’s world with hope: they inspire through clarity of vision, optimism, and profound belief in their— and their people’s—ability to turn dreams into reality. Great leaders face sacrifice, difficulties, and challenges, as well as opportunities, with empathy and compassion for the people they lead and those they serve.” (Page 3)

Why is resonance so difficult? We think it has something to do with the nature of the job and how we manage it. Even the best leaders— those who can create resonance— must give of themselves constantly. For many people, especially busy executives we work with, little value is placed on renewal, or developing practices—habits of mind, body, and behavior—that enable us to create and sustain resonance in the face of unending challenges, year in and year out. In fact, it is often just the opposite. Many organizations overvalue certain kinds of destructive behavior and tolerate discord and mediocre leadership for a very long time, especially if a person appears to produce results. Not much time—or encouragement—is given for cultivating skills and practices that will counter the effects of our stressful roles.” (Page 5)

“In our work with executives we have found that true renewal relies on three key elements that might at first sound too soft to support the hard work of being a resonant leader. But they are absolutely essential: without them, leaders cannot sustain resonance in themselves or with others. The first element is mindfulness, or living in a state of full, conscious awareness of one’s whole self, other people, and the context in which we live and work. In effect, mindfulness means being awake, aware and attending—to ourselves and to the world around us. The second element, hope, enables us to believe that the future we envision is attainable, and to move toward our visions and goals while inspiring others toward those goals as well. When we experience the third critical element for renewal, compassion, we understand people’s wants and needs and feel motivated to act on our feelings.” (Page 8)

“People who think they can be truly great leaders without personal transformation are fooling themselves. You cannot inspire others and create resonant leaderships that ignite greatness in your families, organizations, or communities without feeling inspired yourself, and working to be the best person you can be. You must ‘be the change you wish to see.’” (Mahatma Gandhi).

“The trouble is that personal transformation is not easy. Facing your own shortcomings is hard work indeed. Honesty with ourselves breeds vulnerability. When we see who we really are and do not like it much, it hurts. Contrary to popular belief, it is not change itself that is so hard; what is hard is being honest with ourselves, looking at ourselves with no filters and admitting that we need to change. Many of us shy away from this honesty, just to vulnerability and, yet, the pain that comes with seeing that we are not all that we might have thought, and in fact not all that we want. Self-discovery is really hard work. Maybe that is why so few people do it, and why so few people are really great human beings and great leaders.” (Pages 201-202)

Le succès de la Pleine Conscience en entreprise

8 novembre 2016

Les pratiques contemplatives – la pratique de la Pleine Conscience ou du mindfulness en particulier – sont accueillies par un nombre croissant d’entreprises en Suisse et en France. Cela fait plusieurs années déjà que je travaille au sein d’entreprises, tant avec les collaborateurs qu’avec les équipes de direction ou encore les étudiants MBA du Trinity College à Dublin. Le constat principal est que, en cette ère digitale, le recentrage et la connexion avec soi-même sont essentiels.

Ces pratiques sont souvent présentées aux entreprises comme des outils visant à être moins stressé, plus concentré et plus efficace. Il est vrai que l’art de la Pleine Conscience atteint ses résultats. Toutefois, plusieurs dimensions essentielles, aussi riches pour l’entreprise que pour les hommes et femmes qui y travaillent, sont oubliées. Il est démontré que ces pratiques permettent la justesse dans la prise de décision, une connaissance de soi plus affinée, et le développement de la capacité à mieux “prendre soin” de ses collègues et de ses collaborateurs de façon bienveillante.

UNE PRATIQUE: DIVERSES CONSEQUENCES

Cette dernière dimension est particulièrement cruciale pour l’harmonie collective au travail et l’épanouissement de chacun. Or, l’entraînement à la bienveillance est régulièrement oublié, et ce même parmi les professionnels, sous la fausse supposition que la capacité à “prendre soin” des autres se développe naturellement avec la pratique de la Pleine Conscience.

Mon programme intitulé « Contemplaction pour Avocats », soutenu par l’Ordre des Avocats de Genève, inclut ces pratiques de bienveillance, dont l’effet est remarquable. Les avocats, selon une étude de John Hopkins (1995), réussissent leur carrière grâce à leur faculté de prévoir les problèmes, de critiquer et de rejeter la faute sur la partie adverse. Cette méthode nuit à leurs ressentis ainsi qu’à leurs relations avec leurs collaborateurs et leurs familles. La pratique de la bienveillance leur permet de redécouvrir une qualité relationnelle imbibée d’intérêt et de bienveillance, qui, à son tour, permet de meilleurs résultats.

Les recherches du Professeur Davidson de l’Université de Madison (USA) et d’Antoine Lutz, aujourd’hui à l’INSERM à Lyon, ont montré qu’entraîner son esprit à la bienveillance mène à des changements fonctionnels et structuraux du cerveau et du comportement. Les travaux en cours de Tania Singer, Institut Max Planck de Leipzig, indiquent que la pratique de la Pleine Conscience ne suffit pas à augmenter les comportements pro-sociaux, à l’inverse, de la pratique de la bienveillance qui les augmente de manière spectaculaire.

DES ENTREPRISES INNOVANTES

En intégrant la pratique de la Pleine Conscience bienveillante dans son ADN, l’entreprise renforce ses chances de créer des liens humains forts et harmonieux. En déployant des initiatives de grande ampleur intégrant cette dimension et l’art du mindfulness pour cultiver le bien-être, l’harmonie collective et la confiance, certaines entreprises telles que Sodexo ou la MAIF ont bien compris l’importance de cette pratique. Même si ce n’est pas leur motivation première, elles savent que ce sont des facteurs essentiels pour une performance durable.

UN ENJEU EGALEMENT SOCIETAL

Ce sujet nous tient particulièrement à cœur puisque l’enjeu, au sein des entreprises, n’est pas uniquement individuel ou collectif. Cet entraînement à la bienveillance est aussi la clé d’un engagement altruiste plus marqué des entreprises face aux défis sociaux et environnementaux actuels, notamment la perte de sens, la pauvreté extrême et la crise environnementale. Il détermine un engagement libéré de la pression du public ou de l’Etat, nourri par une détermination forte à inventer de nouvelles formes de business et de nouveaux produits et services répondant à ces enjeux.

Bienveillance & Performance – la nouvelle entreprise

22 avril 2016

La question des conditions de travail est plus que jamais sur la table avec le projet de réforme du travail porté par le gouvernement. D’autant plus quand on apprend, que les Français sont les plus démotivés au travail, selon une étude Ipsos-Steelcase portant sur 12 500 salariés dans 17 pays. Une occasion de revoir les méthodes de management et de travail en elles-mêmes pour redonner le goût à être productif et heureux de l’être.

Les bienfaits de la bienveillance en entreprise

L’environnement de travail serait donc un élément cible de réussite au travail. Mais pas seulement. En 2012, Google s’est intéressé aux causes de l’efficacité au travail et a ainsi lancé une grande étude – le projet Aristote – sur des centaines de groupes de travail afin de mieux comprendre les facteurs influençant la productivité des employés au travail. Après plus d’une année de recherches, statisticiens, psychologues et ingénieurs en sont arrivés à une conclusion des plus surprenantes mais pourtant des plus simples : il s’avère que la gentillesse au sein des équipes de travail semble être le facteur de réussite prépondérant.

Dit autrement, c’est le principe de « sécurité psychologique » de l’employé qui est ainsi mis sur la sellette. La sécurité psychologique implique l’existence d’un sentiment de confiance au sein d’une équipe de travail. Amy Edmondson, professeure de management, la décrit comme « le fait que les membres d’une équipe pensent qu’ils peuvent prendre des risques interpersonnels en toute sécurité ». Pouvoir s’exprimer sans être jugé ou sanctionné, établir un climat de confiance et de respect mutuel, notamment entre responsables et employés, telles seraient les clés de la réussite au travail.

L’étude Ipsos-Steelcase révèle que 75 % des employés en situation de stress vont diminuer leurs performances au travail. Et parce que chacun ne dispose pas forcément des aptitudes nécessaires pour établir ces relations, des formations au « management bienveillant » sont ainsi mises en place à destination des responsables d’équipes et des chefs d’entreprise. À l’université de Saint-Étienne, un master 2 en distribution est maintenant proposé avec un module de management bienveillant.

Une nouvelle tendance dans le management ?

Ces statistiques démontrent l’importance de prendre en considération les besoins psycho-émotionnels du management et du personnel. Plus particulièrement, la direction et les managers renvoient au rapport à l’autorité, aux figures parentales et au besoin d’être aimé. Avec l’évolution des technologies et de la dématérialisation du monde du travail, les rapports personnels-professionnels sont de plus flous. Ceci implique une perspective managériale plus large et une remise en question des pratiques pour la gestion du personnel.

Je propose, à ces fins, deux modules de formation « Performance & bienveillance« , faisant partie de la série de formation PRO-X – Pleine Conscience pour entreprise, qui se consacre au développement de ces compétences:

- Pour les décideurs

- Pour les collaborateurs.

Voir aussi la conférence « Power and Care » à Bruxelles en septembre 2016.

Pont entre sagesse et business – les avocats du barreau genevois méditent

1 décembre 2015

Article paru dans Le Temps, 30.11.2015.

Présentation du programme Contemplactif pour avocats: « Les sciences contemplatives en action au service du droit »

Mindful Leadership Training in Demand

4 novembre 2015

I have now been included in the teaching faculty of the Trinity College Dublin year-long MBA executive programs. The use of mindful practices like meditation and introspection are taking hold at such successful enterprises as Google, General Mills, Goldman Sachs, Apple, Medtronic, and Aetna, and contributing to the success of these remarkable organizations. Here are a few examples:

- With support from CEO Larry Page, Google’s Chade-Meng Tan, known as Google’s Jolly Good Fellow, runs hundreds of classes on meditation.

- General Mills, under the guidance of CEO Ken Powell, has made meditation a regular practice.

- Goldman Sachs, which moved up 48 places in Fortune Magazine’s ‘ »est places to Work List », was recently featured for its mindfulness classes and practices.

- At Apple, founder Steve Jobs — who was a regular meditator — used mindfulness to calm his negative energies, to focus on creating unique products, and to challenge his teams to achieve excellence.

- Thanks to the vision of founder Earl Bakken, Medtronic has a meditation room that dates back to 1974 which became a symbol of the company’s commitment to creativity.

- Under the leadership of CEO Mark Bertolini, Aetna has done rigorous studies of both meditation and yoga and their positive impact on employee healthcare costs.

What is Mindfulness?

Mindfulness is often defined as ‘non-judgmental, moment to moment awareness’. As leaders, it can also be thought of as the cultivation of leadership presence. Being present is quite a complex assignment in a world and global economy that measures time in internet seconds, conceives of the past as the most reliable tool for analyzing and assessing how to proceed into the future, is increasingly interdependent and relational, and dedicates little or no time toward the development of presence in its leaders. But presence can be cultivated and is necessary for a leader to bring all of his/her mind’s capabilities to leadership.

What is a Mindful Leader?

Leadership presence is a tangible quality. It requires full and complete nonjudgmental attention in the present moment. Those around a mindful leader see and feel that presence. A mindful leader embodies leadership presence by cultivating the central quality of centredness. Centredness is a quality of being where one is intimately aware and aligned in one’s inner senses, values and actions in the world. Five qualities support this alignement:

- Calm: a serene mind helps assign the appropriate value to events, people and objectives.

- Clarity: inner spaciousness and clear comprehension helps with decision-making processes.

- Creativity: Gaining perspective in one’s mind and environment, one can think outside the box.

- Courage: leadership requires taking a stance, being bold and making a first step which often makes one vulnerable. Mindful leadership makes one accepting and appreciative of one’s sensitivities.

- Compassion: social intelligence, one of the foremost leadership qualities, is developed through empathic understanding, creating a following of employees inspired by loyalty and commitment.

Meditation is not the only way to be a mindful leader. Bill George (Harvard Business School Professor) reports that his students biggest derailer of their leadership is not lack of IQ or intensity, but the challenges they face in staying focused and healthy. To be equipped for the rapid-fire intensity of executive life, they cultivate daily practices that allow them to regularly renew their minds, bodies, and spirits. Among these are prayer, journaling, jogging and/or physical workouts, long walks, and in-depth discussions with their spouses and mentors.

The important thing is to have a regular introspective practice that takes one away from one’s daily routines and enables one to reflect on their work and their life — to really focus on what is truly important to them. The cultivation of passion and stillness through Mindfulness Meditation helps achieve just that.

A World Ethic

Our world needs mindful leaders, people who embody leadership presence. We need leaders who not only understand themselves but who are not afraid to be open-hearted and who have the strength of character to make ethical choices. The problems we see all around us are not insurmountable, but they do require a new kind of leadership.

As you continue to practice, and find more and more ways to actually be here for your life, you are also likely to encounter more and different ways to influence the lives of others, in your team, in your organization, in your families and in your community. One small step changes the dance, and one small change has the potential to create a better world.

Pro-X Program Descriptions.pdf

Afghan Mindfulness Self-Care Training Results

7 mai 2015

In line with International Medical Corps’ global strategic objective to improve, maintain and scale up highly accessible, high quality Mental Health and Psychosocial programming, a burnout prevention (self-care) program for carers at IMC Afghanistan’s Mental Health Hospital (MHH) in Kabul.

Through sustainable healing methodologies, I conducted mindfulness training for MHH’s mental health staff. This training intended to build on existing positive coping strategies and self-help tools to overcome stress and support positive coping mechanisms of staff. By helping trainees become familiar with their own psychological, emotional and social reactions to trauma, stress and relevant co-morbid conditions (i.e. fear, grief, stress, depression, anxiety), they can develop greater compassion satisfaction and burnout can be significantly reduced. This case study will highlight IMC’s self-care empowerment model, assessment results, lessons learned, and recommendations for improvement and replication in other countries.

Regarding staff working with the traumatized (e.g. doctors, mental health counselors, psychiatric nurses and psychologists) emotional exhaustion was present in 20% of expatriate staff from aid agencies and 10% of professionals.[i] Also, there is considerable evidence that the stress inherent in health care negatively impacts health care professionals.[ii] The researchers list numerous negative impacts from this stress including depression, decreased job satisfaction, psychological distress, and many other physical health problems such as fatigue, insomnia, heart disease, depression, obesity, hypertension, infection, carcinogenesis, diabetes, and premature aging.[iii] This phenomenon is known as compassion fatigue (CF).

CF also associated with decreased patient satisfaction, ‘‘suboptimal self-reported patient care’’, and longer patient- reported recovery times.[iv] Similarly, research shows that stress affects the quality of care through a decrease in attention, reduction in concentration, impingement on decision- making skills, and reduction in providers’ abilities to establish strong relationships with patients.[v] Studies were done on Canadian frontline health care workers (counselors, children’s aid workers, and emergency staff) and found that CF can manifest in the workplace and client relationship through chronic absenteeism, low morale and decreased quality of care.[vi] Further, White (2006) found that up to 50% of practitioners were affected by burnout stemming from CF.

Preventing Compassion Fatigue: Importance of Self Care

Despite the prevalence of CF in the field of social work, researchers have suggested that CF is not only treatable, but preventable.[ix] The ability to address CF before onset would allow trauma practitioners to provide consistent high quality care. Empirical studies have shown that there is a circular relationship between CF and self-care.[x] They stated that “professional caregivers tend to be very good at caring for others, while often neglecting and failing to recognize their own needs” (p.4). Research shows that clinicians who make a conscious effort to look after their own well-being are not only less susceptible to CF, but have a greater sense of compassion satisfaction.[xi] Research indicates that having a higher level of compassion satisfaction (getting satisfaction out of helping others) enables clinicians to be more effective in treating their clients. A major contributing factor to the development of compassion satisfaction is self-care.[xii]

Self-care is defined as an unbiased observation of one’s inner experience and behavior, as well as the responses that counterbalance negative factors. Facets of self-care include self-awareness, self-regulation/coping, and balancing of self and others interests[xiii]. Examples of self care include psychotherapy for the caregiver, supportive work environment, proper supervision, and peer consultation. In addition, contemplative (meditation, mindfulness and self reflection) techniques have been highly successful in the reduction of burnout.[xiv]

The Mindfulness-Based Counselling (MBC) program was originally planned as a 3-phase Training of Trainers (ToT) intervention: (i) mindfulness self-care skills, (ii) Mindfulness-based counselling skills, (iii) trainer’s module. Since it was a pilot project, and due to the finishing assignment of International Medical Corps (IMC) at the MHH, we completed only the first phase of the intervention (self-care).

Training Objectives

The objective of the intervention was to develop and strengthen IMC’s mental health self-care strategies, as part of the rehabilitation program of quality hospital standards of MHH. Through sustainable healing methodologies, Mindfulness training was conducted for MHH’s mental health staff. This training intended to

- build on existing positive coping strategies and self-help tools to overcome stress and

- support positive coping mechanisms of staff. Also, the training aimed at

- helping trainees become familiar with their own psychological, emotional and social reactions to trauma, stress and relevant co-morbid conditions (i.e. fear, grief, stress, depression, anxiety),

- while respecting the Islamic cultural context and making specific reference to it.

- be planned over three phases, two of which were distance-based.

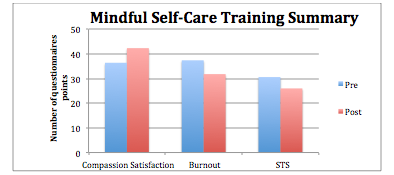

Overall, the training evaluations indicated a positive outcome for the training. Compassion satisfaction and mindfulness skills were increased, burnout and secondary traumatic stress were reduced. Since self-care was a new methodology and way of practice the counselling profession, it was a challenge for participants to value that by taking care of themselves, the services they provide to the beneficiaries are positively affected. More specifically, mindfulness practices were well received and understood, and the small group distance-based format of the training worked well with uninterrupted skype conferences.

|

|

For the full report, please click contact Boaz here.